Unless you work in higher ed, you may not have heard the term critical consciousness. Developed by Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire, it first appeared in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, published in 1968. Freire saw education as being inextricably linked with social justice and “described critical consciousness as a powerful tool for societal transformation by motivating individuals to combat oppression, violence, and dehumanization within their communities” (Seider & Graves, 2020, p. 3).

Because Extension Engine designs learning experience platforms for a variety of learners, an understanding of critical consciousness is helpful in our work. It can inform everything from the construction of a platform to the terminology we use within it. For Senior Learning Experience Designer Katie Novick Nolan, it’s a key consideration going into any project. As a former social worker who has also taught social work courses, she understands the importance of interweaving equity and social justice theories into learning experiences. Katie sees critical consciousness as one of the most impactful theories, particularly as it’s presented in Scott Seider and Daren Graves’s book Schooling for Critical Consciousness: Engaging Black and Latinx Youth in Analyzing, Navigating, and Challenging Racial Injustice. She says, “[This book] was so deeply inspiring to me because it laid out in such a clear way not just what this theory was but why it was powerful and how it could be utilized in the real world, versus sticking to theory.”

The Importance of Stories

Stories are at the heart of any critical consciousness practice because, as writer Joan Didion famously said, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” These stories can come from many different places, but often at least some of them are what are known as stock stories. While not specifically a part of critical consciousness theory, stock stories and their opposites, known as counterstories, provide a useful way to understand the social analysis that’s a necessary part of critical consciousness.

Stock stories are described as “those which people in positions of dominance collectively form and tell about themselves. These stories choose and pick among available facts and present a picture of the world that best fits and supports their positions of relative power (Delgado, 1989, p. 2421)” (Martinez, 2014, p. 70). These stories are presented as truth, as if they’ve been constructed by an objective third party, which is impossible, since no one can be completely objective. Katie says these are sometimes called “thin” stories, which are invested in maintaining the status quo.

Counterstories, as suggested by the name, work against dominant stock stories. “Counterstory, then, is a method of telling stories by people whose experiences are not often told. Counterstory as methodology thus serves to expose, analyze, and challenge stock stories of racial privilege and can help to strengthen traditions of social, political, and cultural survival and resistance” (Martinez, 2014, p. 70). Counterstories are a way to open up the narrative. Once we can recognize stock stories as constructions and not objective truth, they will lose their power as we start to see how they are mechanisms for maintaining oppression through the current systems.

One example of this is the story of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), as told in the documentary Holding Ground: The Rebirth of Dudley Street. It’s about a marginalized neighborhood in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in which community members and activists wanted to push back against how they were being treated by local government, the media, and some businesses. So they went to their neighbors with a survey to find out what they cared about most. They found that one of the major problems was vacant lots in which companies were illegally dumping trash because people saw Dudley Street as a place where they could do that and get away with it. The dominant story was that no one cared. So the DSNI set about changing that narrative. As one DSNI member stated, “The Don’t Dump on Us campaign was a message to a lot of folks including City Hall, including the media and others who were trashing this neighborhood in more ways than one.” In other words, this campaign was the counterstory.

The DSNI held community meetings and protests, they printed pins, and they pushed back. Over time, their efforts worked: they changed that dominant stock story by getting enough attention on their counterstory, and their efforts stopped the illegal dumping, contributing to the overall improvement of the neighborhood.

The Components of Critical Consciousness

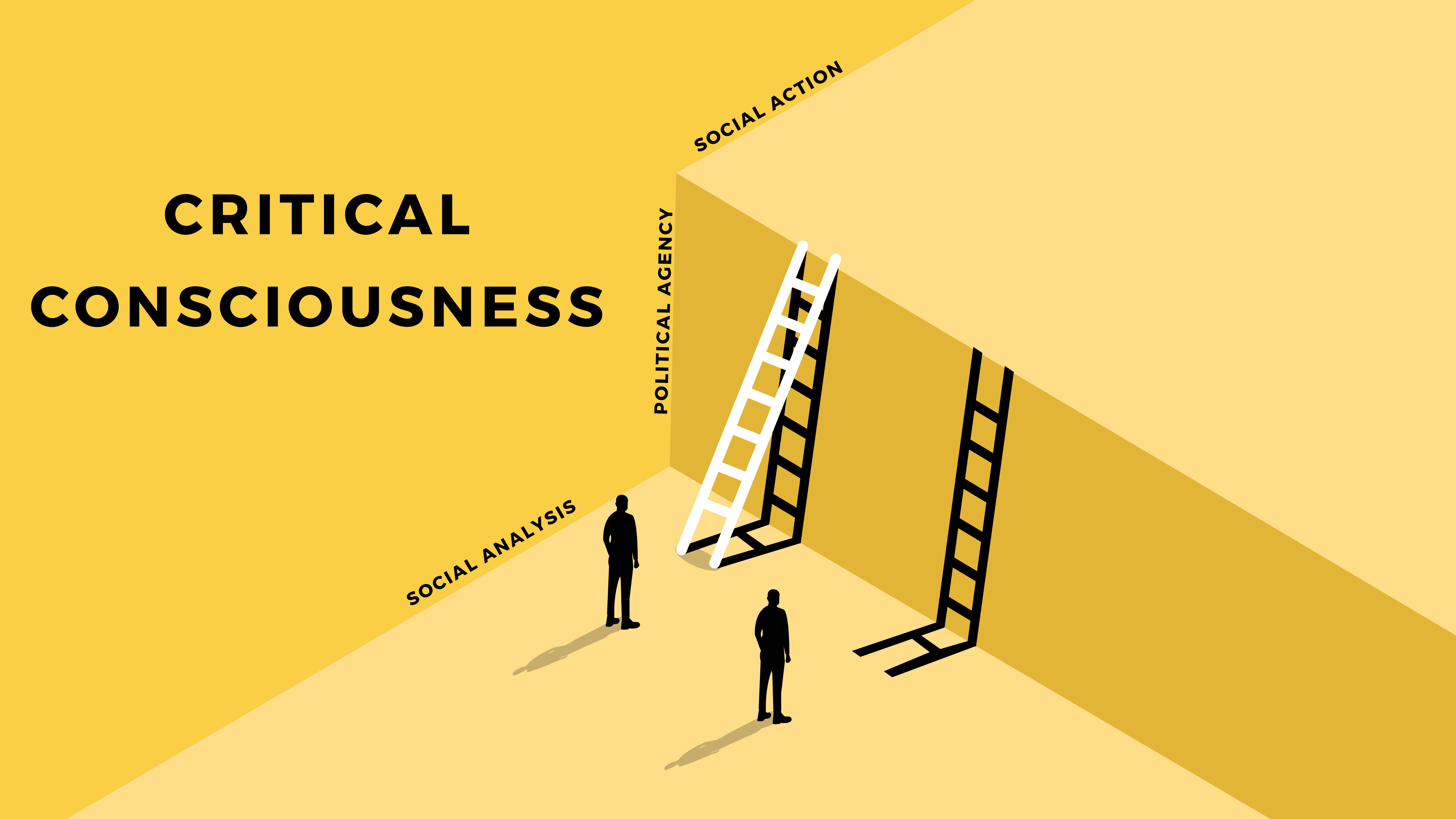

Once you know what stories you’re looking at and who’s telling them, the three components of critical consciousness come into play. They are the following, as described by Seider and Graves:

-

Social analysis

-

Political agency

-

Social action

Each of these three components is equally important. “All three pieces work together and need each other,” Katie explains. “Social analysis is about fostering critical-thinking skills, and specifically critical-thinking skills that allow you to analyze things on more of a systemic level and understand how inequality might be functioning within a system. Social action is actually taking action within that system to create positive change, and that can take a lot of different forms depending on each person’s unique strengths and things that resonate with them. Political agency is this idea that people need to be able to bridge those and believe that they’re capable of creating change in these systems, and that is a really important piece, like the secret sauce. If you just have social analysis and you don’t have action, that can be a really despondent place to be; and vice versa, if you’re like, yes, social action, and you don’t engage in social analysis, you can be destructive.”

When critical consciousness is explored and taught in the classroom, Seider and Graves (2019) found that it helped students by forming what some researchers call psychological armor that protects adolescents from “the negative effects of oppressive social forces such as racial injustice” (Phan, 2010, p. 1). As Katie says, “Theory can be so powerful, but theory put into action is really unbelievable.”

This is a summary of an example from Schooling for Critical Consciousness

This is a summary of an example from Schooling for Critical Consciousness

Critical Consciousness and Learning Experience Platforms

As for how critical consciousness can be applied in the work Extension Engine does, there are a few points to consider.

-

Because critical consciousness can be taught and its benefits can be significant for the learner, it may be possible to use it within a learning experience platform. “Obviously it has to be appropriate to the learning experience, but this actual content can be valuable in different ways to be incorporated into learning experiences,” Katie says.

-

The theory of critical consciousness can be used when creating learning experiences even if it’s not explicitly part of the experience. Katie gives the example of co-constructing learning with potential learners and doing user testing with critical consciousness in mind. The goal is to end up with a tone, approach to engagement, and sense of community building that will welcome all learners.

-

Awareness of critical consciousness while building platforms is worthwhile, even if there’s no way to directly use it within the learning experience. “With all the best intentions, we all have biases,” Katie says, “and so a framework like this helps us continue to engage in social analysis and to understand how our own values, our own beliefs, our own upbringings, our own dominant culture messages are influencing what we think is important, how we’re talking about it, the examples that we use, and can hopefully help keep us in a space where we’re valuing more inclusion.”

Further Reading/Watching

-

Aja Y. Martinez, “A Plea for Critical Race Theory Counterstory: Stock Story vs. Counterstory Dialogues Concerning Alejandra’s ‘Fit’ in the Academy” from Performing Antiracist Pedagogy in Writing, Rhetoric, and Communication, edited by Frankie Condon and Vershawn Ashanti Young

-

Holding Ground: The Rebirth of Dudley Street documentary